In some states, you are not allowed to dance in prison.

You are also not allowed to touch another human, which includes high fives, handshakes, and hugs. And sometimes, you are not allowed to move from your bunk for long periods of time while the facility goes on lockdown or the guards attend off-campus employee appreciation luncheons for multiple days in a row.

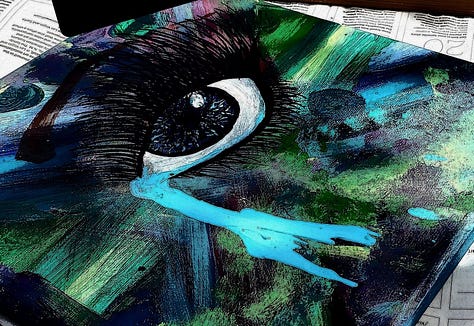

In prison, your body is no longer your own.

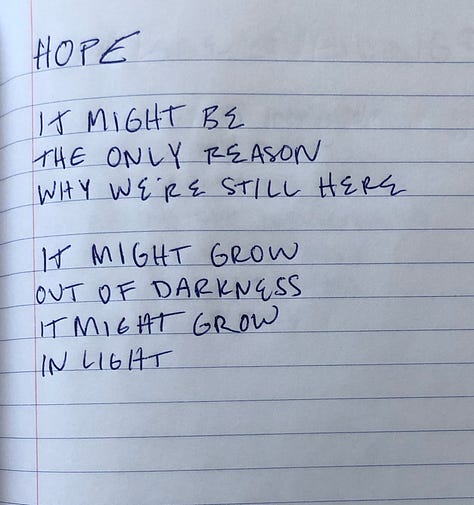

Except perhaps for one hour on Tuesdays, when my friend

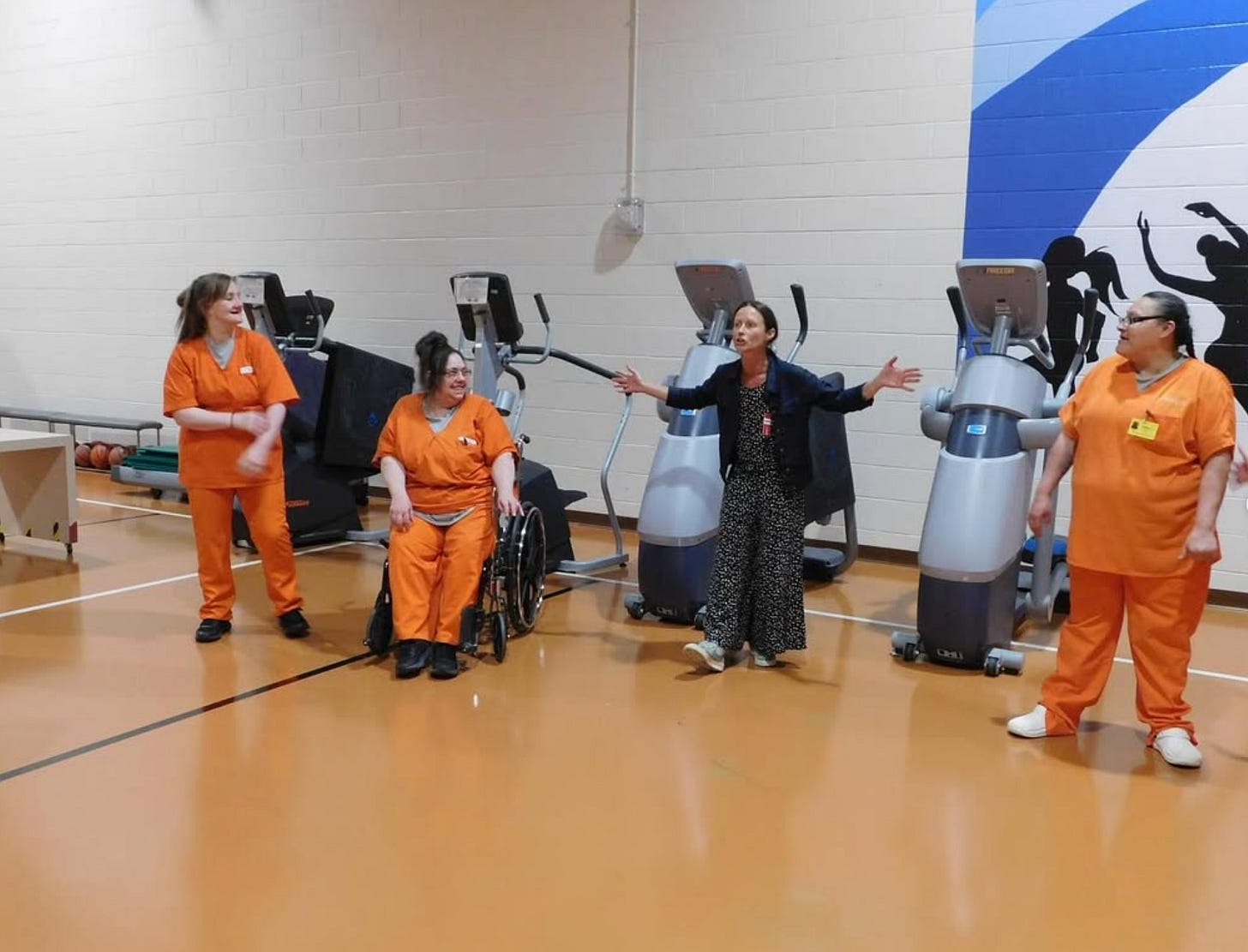

facilitates yoga, breathwork, and movement classes. Nikki has been facilitating classes at Coffee Creek Correctional Facility through her nonprofit On the Inside for over seven years and recently, I was lucky enough to get to tag along. When asked about her classes, I often hear Nikki say: I don’t teach anything that won’t make your life better.On this particular Tuesday, Nikki and I arrive at the prison wearing roomy t-shirts and sweatpants, as carefully instructed in the visitor guide. We are not allowed to wear the color blue, a shade exclusively reserved for inmates. After we pass through a chain-link fence, we enter the intake office where an austere blonde woman triple checks our ID. There’s a slight delay as she tries to find my clearance papers, and I catch myself over-smiling. When we’re finally buzzed into the yard, I realize I’ve been holding my breath. I feel astonishingly anonymous—no phone, no ID—as if I could disappear here.

Coffee Creek has a pleasant name, but it’s a granite universe. A concrete palace of clocks, walkie talkie chatter, beeps, and intercom calls. Everything in the facility has generic names like E3, Bunk 7, The Yard. Even the inmates are known only by their last names or their numbers—Inmate 12, 45, or 107. The air reeks of bleach.

We tend to imagine prison as a place of correction, but it is rarely rehabilitative. Instead it offers its own topography of trauma. Incarceration often involves sending traumatized people to highly traumatizing environments and expecting them to somehow heal. In prison, your body is made small and your suffering visible. There is never a door to close or a place to hide. Your pain is constant and is constantly observed. When I led workshops for young girls who were victims of human trafficking and often spent time in detention centers, they ranked their experience in juvie as often higher in traumatic impact than even their sexual abuse.

In preparation for class, Nikki and I haul mats to the activity room, and when the women arrive, they enter softly—dressed in blue, hair pulled back in ponytails, makeup-less with high white socks. Once seated, Nikki asks each woman to say the name they’d like to be called. They offer their first names or chosen nicknames—Angela, Ellie, Twitch, Pat. One of the women jokingly identifies herself as Bacon and Eggs, and I never decipher why, but it spreads around the room with familiarity and delight. Nikki instructs the group to call on one another to go next. I want them to say each other’s names, she tells me later, and I want them to hear their name being said.

Many of the women at Coffee Creek are incarcerated for similar offenses: burglary, fraud, armed robbery, drug crimes. Often, they’ve been convicted of violence in acts of self-defense against men who abused them. But here, in Nikki’s class, no one talks much about the past. The women talk about what they want to do when they get out, how they want to hold their babies again, eat fresh fruit, or finally get clean.

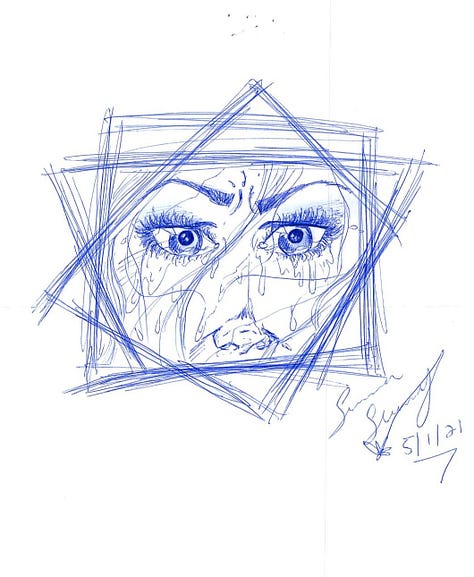

Nikki asks the group: If your heart could talk, what would it say? The women, warmed by hearing their names aloud, answer:

My heart says I’m doing a good job.

My heart says: I love you. Go forward.

My heart is telling me —Thank you for taking care of me, finally.

Nikki’s yoga class is unlike any I’ve ever been to, and it’s possibly my favorite ever. There’s laughter and muttering and a lot of falling over. You wouldn’t expect tenderness in prison, but suddenly it’s everywhere. Bacon and Eggs winks at me in vinyasa and whispers that I look like Joy from Inside Out. Between the poses, one woman lets out a sigh so low and burdened, I feel it in my chest even now.

Poet and novelist, John Berger writes:

One of the essential elements in tenderness is that it’s a free act, a gratuitous act, it has an enormous amount to do with liberty, with freedom because one chooses to be tender. In the face of what is surrounding us, tenderness is almost a defiant act of freedom.”

And it’s true —it’s here—in the concrete of Coffee Creek. The tenderness insists that we’re human, all of us, and there is no real difference between our lots other than dumb luck. After class, the women return to their bunks for another lockdown, but I overhear one woman quickly tell Nikki—“I needed this. I’ve been afraid to file for a divorce. Now I’m ready.”

Nikki’s work is truly some of the most crucial I’ve seen. Not only does she provide ways for expression and inner knowledge in spaces of oppression, but she teaches resilience. She helps women trust one another again in a safe container. She reminds them that they are worthy of liberation and healing. More than once, an incarcerated woman has postponed her release date so she could attend one final class with Nikki. Tenderness like this is hard to find, even on the outside.

Nikki's team teaches 5 weekly classes in Oregon alone and 13 weekly around the world. She works with a team now of 6 facilitators—supporting women and youth to grow, heal, and change. Half of her team have been previously incarcerated and now uses her facilitation model to mentor women out of cycles of self-harm, addiction, and incarceration. This work begins in prison and ripples out into communities, cities, and the world.

On our way out, Nikki shakes her head: The absurdity of a prison making it illegal to dance is that if you can’t dance, you can’t express yourself. If you can’t stretch, you can’t release. As we wait to be buzzed out, a lump rises in my throat. She sighs: You simply can’t heal the body without moving it. So every class, I’m going to help these women move.

Nikki and I pass through the final barbed wire gate and exit into sunlight. As we hug goodbye, we say one another's names.

P.S. On the Inside is doing the necessary, re-humanizing work within prisons. In a space where women are reduced to inmates and routinely degraded, Nikki’s work isn’t just helpful, it’s some women’s only chance at healing.

In a moment in our country where we are seeing mass cruelty, growing despair, and the denial of each other’s dignity, join me in tangibly supporting this work of healing and restoration. Join me in offering tenderness as an act of defiance. Together, let’s insist on one another’s humanity.

I’m raising 3K to help Nikki update her website so she can continue approaching more foundations to help sustain this crucial work. Especially now, funding is deeply difficult to get. Our goal is 3K, but, honestly, I’d love to blow that goal out of the water. Any additional funds will go directly to helping Nikki and her team launch a new program that offers mothers and families long-term support both during incarceration and reunification.

If you’re able to give a small donation to support this work, we would be so immensely grateful. And so would Angela, Ellie, Twitch, Pat, Bacon and Eggs, and all the other women on the inside.

**All photos have been taken and shared with consent.

As someone who was inside, it does my heart so good to see these stories being shared and work being done. Those classes are lifelines, those moments where we are known by name some of the most profound beacons of existence beyond those walls. Thank you for sharing and the work you are doing, it matters so very much…more than words could ever say 🙏

This broke my heart and made it whole. Thank you, Joy x